Education, Spirituality, Church and the Feminine.

On Thursday 28th April Mrs Raffray was guest speaker at the National Board of Catholic Women (NBCW). This was a wonderful opportunity and Mrs Raffray seized it with both hands, speaking on ‘Education, Spirituality, Church and the Feminine’, an extraordinarily inspirational talk.

The NBCW says, ‘As a body with representatives from many national organisations we strive to give Catholic women a voice at national and international levels. We actively promote the presence, participation and responsibilities of Catholic women in the Church and society.’

Formed in 1939, the NBCW ‘brings together women from many different backgrounds. We work nationally and internationally to challenge discrimination and promote the right of women to gender justice. We actively promote the presence, participation and responsibilities of Catholic women in the Church and society. We work ecumenically with women of other faiths and secular groups. Our many member organisations, with their particular interests and networks, make an invaluable contribution to the work of NBCW. NBCW give a voice to Catholic women.’

The evening began with talented St Augustine’s Priory musicians Roza and Ilona singing, ‘The Song of Ruth’ based on the Book of Ruth a story of women’s loyalty and faithfulness. The text of Mrs Raffray’s talk is as follows:

“I have structured my talk around my own story because I realise that my formation as a Catholic leader is also a reflection of how the experience of growing up as a Catholic woman has changed dramatically since the last century. This has been hastened by a pandemic, the all-consuming online world and the invisible and decidedly not neutral algorithms which control us in ways we do not even comprehend.

One of the greatest challenges for our time, for connecting “education, spirituality, Church and the feminine”, is that those elements have become more siloed – in the UK the secular, self-referential world dominates, there are fewer and fewer priests and religious, the pandemic has reduced the number of people attending Mass, families do not automatically seek Catholic schools, the development of feminist theology is not welcomed universally and the guidance given to schools as they manage canon law is so highly charged that we need to find a new level of dialogue, not debate, to make sure we enter the next century with a vision which is integrated, inspirational and transformational. We are the Easter people, after all.

I went to an all-girls school in Birmingham in the 1980s – it wasn’t Catholic, but as a teenager I was formed by a youth group inspired by St John Paul’s visit to England – a group called Lumen Mundi – light of the world – we met twice a week in the rooms of our local church which was also a house for Brothers training for priesthood at Oscott. We knew this was special – we met twice a week – once to practise music for Mass – we sang and played hymns all the time. We also met for talks, and to explore our faith – we probably received some of the lectures the Brothers were receiving. We prayed, led our own retreats, we went youth hostelling and sang the good news from the mountain tops and I found a voice for prayer and for ethical discussion which I was able to take out into the world. We took seriously the inspiration of the name Lumen Mundi and it shaped the adult that I am and the way my leadership of Catholic education has developed. Fortunately so, because we did not know then that, as lay people, we would be a last generation to know so many priests and nuns. In education, we are well past the first generation of Lay Heads and Catholic Heads are now charged not just with exam and inspection regimes but with the transmission of the faith in a way which carries more and more responsibility.

My formation as a Catholic was in a parish where we were surrounded by young men with strong vocations, being formed themselves, and because we were willed on by the adults around us, and the priests who more than tolerated us invading their space, who themselves were at the forefront of social justice, my sense of Church was of a place which was invitational, equipping us to use our lives to change the face of the earth.

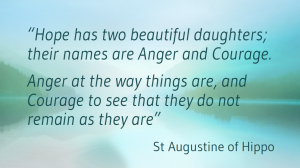

We all read Gerard Hughes’ God of Surprises and we all believed heart and soul that if we were not part of the solution we were part of the problem. We introduced the parish to fair trade products and then went off to university and did the same. Without the intrusion of social media, we were blessed with profound encounters, the kind of which Pope Francis speaks in Fratelli Tutti – and a spirituality which grew because we were welcomed, challenged but not judged. We were encouraged to debate and explore alternative viewpoints without fear.

I think we can be proud in Catholic schools of R.E. as a core subject in the curriculum compared with those days. There will always be discussion of what else we could be doing. But from 3 to 18, in Catholic schools there is a real understanding of the teachings of the Church, as well as the theology and the Gospel values which underpin it. Certainly, I think many people would be surprised by the intellectual level of discussion, the academic vocabulary and knowledge which our teenagers now have. There is hope there. There is hope also in the ethical formation, an understanding of the virtues and an emphasis on the Common Good which is inspiring.

However for me, spiritual development which is enriched by the intellectual is the area which is at risk in a world overwhelmed by social media, moral relativism and the potentially reactionary response to church attendance falling. There is a danger that the prophetic voice of the young which is needed will not be accompanied by a spiritual profundity – because schools cannot be parish, family and everything which is asked of us. Chaplaincy in schools achieves wonderful things but cannot replace everything which the parish and family devotions provide.

So I grew up with that backdrop of twice weekly prayer and an openness to the Holy Spirit of weekly talks given by the Brothers, liturgical engagement which later found expression in the Catholic chaplaincy at Manchester University – two Jesuit priests and an FCJ nun there gave challenging sermons and Sr Andrea ran retreats for women to explore their vocation. This included motherhood as a vocation. As Head of a girls’ school I always mention motherhood when I refer to the future and careers. We want girls to become women who are leaders and we also want them to hear us speak of motherhood. They will be mothers of children alive in the 22nd Century. We have to get them ready.

From university studying English and Latin and a PGCE, I started teaching at Xaverian College in Manchester when the Brothers had just left but which rejoiced in a staffroom alive with the inheritance and stories of those religious. From there to St Bede’s College and a culture where men were openly paid more than women, where women were not allowed to wear trousers and the staff room was called “The Masters’ Library”.

As an English student I had rejoiced in the growing movement of feminist literary criticism which was challenging the canon, examining lacunae – absences of women. We were asserting that the male pronoun he did not actually encompass woman. This has been acknowledged in new spaces like the lovely PrayAsYougo app where God is carefully called on with no pronoun. And we could debate that one for hours. If the male author, voice or pronoun is the norm, then women are the other, on the outside, in the margins, the periphery, or plain invisible. Discourse analysts will tell you that if you are talked over or interrupted often enough you grow silent and the history of women arguably is of one long interruption. The silence of women has been accepted for centuries. But at times that borderland position offers new insights, yields new meaning and generates a creativity born of subversion, wit and incisive critiques.

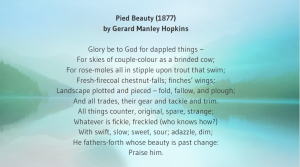

Patriarchal language is so embedded in the Christian tradition that playfulness yields much. Hopkins’ beautiful poem “Pied Beauty” is a great example of this. A paean to creation, to God the immutable creator it climaxes with “He fathers forth……Praise him”. What happens if we change it to “She mothers forth”? Why does it sound bustly and lacking gravitas? More on negative semantic space later. Margaret Hebblethwaite’s Motherhood and God was a real inspiration to me and remains so. Tellingly it is still a book to which people refer. What happens to the Our Father if we say Our Mother, she dared us to ask. These may have been academic preoccupations of the 80s and 90s but the questions remain and the fact that the Pope’s recent encyclical Fratelli Tutti is so named shows not just the heritage of St Francis, but also that not much has changed although the Pope works hard to work around that fact in his writing.

My MA in literature and modernity took this further– an essay on Eavan Boland whose poems explore thresholds – women holding babies on their hips, standing on doorsteps at dawn, or dusk (crepuscular poetics, I grandly called it) was a time to explore what motherhood meant in the abstract (I hadn’t had my boys by then). But I had long been interested in how mothers’ voices and experiences were present or absent in the Bible, in the hierarchy of the Church, in structures, in prayer and in the language of hymns and other texts. I have always been inspired by the exploration of these spaces, interstices – because you can fill a space. It is not competitive, just different. The Easter story is a narrative of women finding an empty cave after all.

I have always loved language – especially wordplay, symbols which engender multiple meanings. The girls’ secondary school I attended made sure that we knew just how lucky we were to be educated and how relatively recently this had happened. In our first year there we had a lesson a week on the history of the school and girls’ education. The lesson was called, hilariously, “The Headmistress’s Period.” It was 1979 and we 11 year olds knew that this was very funny, and out of kilter. It was also the time when every Saturday night men like Val Doonican or Des O’Connor would appear singing – fully dressed while the women dancing beside them most often seemed to wear bikinis. We knew there was a disjunct, an objectification, an inequality every time we turned on the telly even though we didn’t have the words for it. Right now the children in our schools, girls and boys, are fortunately not so silenced when they identify things that make them feel uncomfortable – and the culture of safeguarding is all about giving words to feelings right from the Early Years. But we must make sure that this freedom continues. Students want to talk about gender and inclusion. But Catholic schools have been told in relation to LGBTQ+ that they are not allowed to use the word ally nor can staff wear rainbow badges because it signals allyship. As school leaders we are now exploring not just the feminine and the place femininity occupies, but the very nature of gender. And we are watching language change in action when the word ally becomes politicised and effectively banned. This is a very good example of ways in which words can become barriers to students feeling they are part of the Church. Much of spirituality is about listening. And much of being a Catholic leader of girls is also about listening. We might look at an increased quality of listening in the Church if we hope to bring the young with us. On a personal note, my mother was inspirational and clear with us about Mass and the sacraments mattering. Her last words to me were “listen Sarah” and she didn’t say anything else. For years I was tortured wondering what it was she was going to say… and then a wise friend suggested that she had left me a very clear instruction – “listen Sarah”. I have never forgotten the impact of those words.

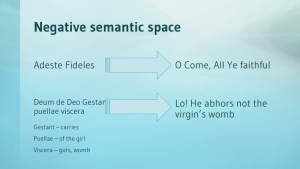

Linguists talk about semantic space – and feminist linguists speak of the way in which women occupy negative semantic space. The hymns and carols we sing have inherited a very masculine universe, a war-like spirituality which reflected either times where war was common or where dominion was the recognised trope for God’s kingdom . I think of marches like ‘For All The Saints’, hymns like “Once to every man and nation”, which were great to sing, preparing men for war or martyrdom –meanwhile, have you ever noticed that ‘As I Kneel Before You’ is a waltz? We had a Director of Music once who played it as a Viennese waltz at one of our Masses at the Abbey in Ealing. The Abbot was quite taken with it and I found him dancing in the sacristy.

The School Carol services for me were times to sit and puzzle over translations of carols. I remember being genuinely baffled by the translation of one verse of ‘O Come All Ye faithful’:

The Latin is `gestant puellae viscerae”

Gestant – nourish, grow

Puellae – of the girl

Viscerae – flesh, entrails

The Latin is wonderful – a girl, flesh – visceral flesh, earthy language, nourish – warm, loving

Somehow in the translations it becomes ‘Lo he abhors not the virgin’s womb’.

The translation is trying to convey the theology – we are singing of the incarnation – in itself a meaty word which because it is Latinate loses that earthy physicality.

The translation reflects a time by which Aquinas had said that women’s role in fertility was to provide the flesh and the man the soul. It reflects a binary world – division, pain and actual ugliness – `abhors not’ is an extraordinarily negative description of conception.

So having been educated to notice how precious education is (thanks to the Headmistress’s Period), being alert to the way in which words are plainly not neutral and then landing in a school where women and girls were implicitly or explicitly excluded, I applied for a job as Head of Sixth Form at St Mary’s Cambridge and there the inspiration and charism of the CJ sisters transformed things with the constant inspiration of Mary Ward – a woman not noted for suffering fools. She was an irritation to Popes, who set up the first order of apostolic nuns, who even as she was dying, rejected and disgraced, wrote “mirth in times like these is next to grace” meant that I knew I had found a place professionally, spiritually and intellectually where there was work to be done for the girls and women in our community.

As it happened, the next school I worked at was also a CJ school – St Mary’s Shaftesbury and there, with other colleagues, we set up a Mary Ward group – there were no longer nuns in the school and we were devoted to ensuring that the legacy of Mary Ward was embedded in every aspect of school life – so that we were living and breathing the spirit of adventure, the edginess of rule breaking (her nuns were known as Galloping Girls) and the embedded practice of prayer which is especially alive in boarding schools. In all Catholic schools, if there is a tragedy, it is to the Chapel that girls turn and there is a confidence there which for non-Catholic girls which is shared. They know their voices matter – they want to take part in all night vigils, in liturgies – to read – whatever faith tradition they are from. They want to sing and be moved by music which stirs their soul. At St Mary’s it was the ‘Song of Ruth’ which spoke to them most powerfully, as was ‘Tell Out My Soul’. Hymns with stories of women’s fidelity, courage, longing, yearning for justice, of travel, displacement, of finding your place in the world. They chose these hymns because they had profound meaning, they were about accompaniment and encounter, not world domination. Girls’ schools don’t have the monopoly on this, but in all three Catholic girls’ schools I have worked in girls sing hymns wherever they are – on the tube our Year 5 girls sang ‘As I Kneel Before You’, an Upper VI group camping out in the school grounds last summer in the absence of other rites of passage put together a playlist in which were hymns like “We will go forth with joy” alongside Ed Sheeran.

And, again it is not the sole prerogative of girls’ schools, but there is a physical ease with the ritual and movement of participation in leading liturgies which I see over and over again in our schools. We are human, our bodies are not an accident or something of which to be ashamed or embarrassed or indeed abhorred. Ask a group of old girls when they return to school for a Mass, to do the offertory or the bidding prayers, and without rehearsal they will process and all bow in sync at the altar and do so with no self-consciousness. I don’t think we reflect enough on the beauty of these connected physical moments in our spirituality, feminine or otherwise. We encounter God in that movement. Just as cognitive development is connected with physical growth and neural pathways so somehow is spirituality, as in schools as we live out those rituals week after week. During the pandemic one of the many agonies was the loss of this grace. At St Augustine’s Priory where I am Head, our Deputy Head developed inspirational retreats online while the girls were stuck at home. We were innovative but as much was lost spiritually for our girls as was potentially missed in other learning. This is not being talked about enough.

So, given girls’ delight in participating in liturgy, we potentially face fracture. The consultation for schools on the Liturgical Directory states that only Catholics may read the readings at Mass and “not even a Methodist may do so” is one of the more extraordinary lines. Our students feel this division and the divisive language. They are as puzzled by it as I was by the translation of that carol all those years ago. Their world is intentionally inclusive and non-judgemental. They are alarmed by language and alert to definitions which are exclusive. They are alienated by it. We know that fewer and fewer families attend Mass and that it falls to Catholic schools to teach the traditions, the catechism. It saddens me that at a time when the world is yearning for healing and a sense of the transcendent, for a God of love, that we could become more closed so that in some schools with very few Catholics we might end up hearing only a few voices. We will all be diminished by this.

I am an inspector for the Independent Schools Inspectorate. One of the outcomes we must evidence is spirituality. When I have inspected non-Catholic schools I have always found gorgeous people, wonderful teachers doing good, but helping students to even identify a sense of wonder and so tick the spirituality box can be a very unnerving experience as an inspector. Most students in non-Catholic schools have no idea what you are talking about. So while there is much we need to do as we emerge from the pandemic, and as we prepare our girls to live alongside robots, to programme those algorithms with integrity and wisdom, to cherish life and to march for justice not dominion, we can be very proud that in our Catholic schools our girls and indeed all young people not only have a knowledge base, but a language for their God, an understanding that they have been put on the earth for some purpose because they are unique and loved. The Head who first said to me “when you are a Head” and all other Catholic Heads and inspirational R.E. teachers and Chaplains who have led me to this place and those with whom I work and am by inspired every day, they all know they are about some great work. So are all the teachers and staff in schools like St Augustine’s Priory where we have been mapping our curriculum to the World Economic Forum Schools of the Future. This embeds sustainability, for example, across the curriculum ensuring such vital learning for future living is not just the job of R.E. teachers.

I have been at St Augustine’s Priory for 10 years now. When I started I was told we didn’t close for Napoleon and we don’t close for snow. We didn’t close for Covid. The Canonesses who founded the school in 1634 in Paris were recusants, big names like Throckmortons. We have a long pedigree of being counter cultural. The nuns moved from their original convent in the centre of Paris for Haussmann’s buildings in 1862 and then, when laicisation laws came out in Paris in 1911, they shifted again to Ealing, building another school as WW1 loomed and as a flu pandemic waited around the corner. There is nothing new in the world. They were independent, indomitable women and one was a suffragette who apparently tied herself to the railings outside Downing Street. The legacy and founding story of women from hundreds of years ago as well as more recent colleagues and old girls – (or anciennes élèves as my counterpart at our sister school in Paris says – no one wants to be a vieille fille), integrates all of our themes tonight. Our sister school St Marie de Neuilly (different nuns now but with the same spirit) tell the stories of courage that we rejoice in – with a French foundation Russian has always been taught in our schools; for example, a Russian teacher at St Marie, a nun, went in and out of Russia to visit family. It was years later that she revealed that on each visit she smuggled out manuscripts of Solzhenitsyn. There really is nothing new in the world. And like those women in schools all over the world before us we will continue to tell our stories, to vision, to envision, to create a post pandemic world – we will mother forth.”