Empowering young minds since 1634

Catholic Independent School in Ealing, London

Abigail joined the Nursery at St Augustine’s Priory at the age of 3. From an early age, she demonstrated a love of learning, becoming a joint winner of the Science Fair in Year 5 and has continued to excel, especially in STEM subjects.

Alessia joined St Augustine's Priory in Year 4 and has grown into a shining example of resilience, leadership, and dedication.

Emily, a devoted farm enthusiast and farm steward, brings genuine care and dedication to the animals at our farm. She joins us on the farm daily, offering her time, energy, and heart to ensure the well-being of the animals.

At 14, Lucia was awarded the Modern Languages Scholarship. She won the Spanish Spelling Bee competition and was a runner-up in the French Spelling Bee. Her linguistic talents also earned her the DELF Diploma at both levels A2 and B1, cementing her status as a triple scholar.

Lily is a prime example of determination and ambition, driven by her long-held dream of becoming a veterinarian. At St Augustine’s Priory, her passion for animals shone through in her active role in the Priory Farm School Farming Community. Her natural affinity with animals, combined with strong academic drive, made her a standout student.

Changing The World

Success & Destinations

2025 A Level Results

- 40% A* Grades

- 67% A* - A Grades

- 88% A* - B Grades

93% of students received confirmed offers from Russell Group universities.

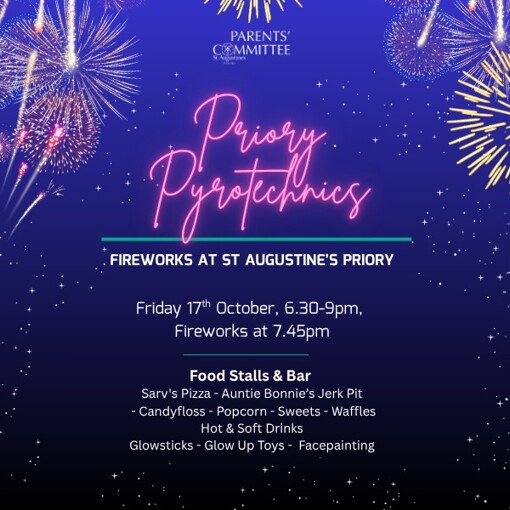

News from Our Community

Latest Events